Writers and Gratitude

Rorgo Fretellus' description of the holy sites in and around Jerusalem - the Descriptio de locis sanctis - was one of the most popular Latin accounts of the Holy Land written during the time of the crusades. First composed in the late 1130s, there remain over a hundred manuscripts that attest to its popularity and wide diffusion. Yet in spite of this wealth of manuscript witnesses, many questions concerning this text and its author remain unresolved, and a critical edition of this work which would take into account its various redactions is still lacking.

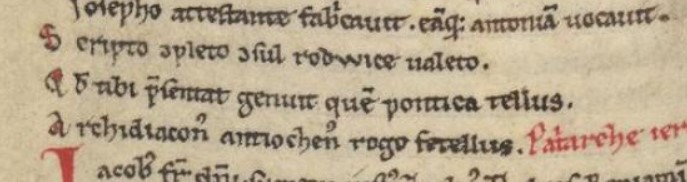

In many of our manuscripts, the Descriptio is prefaced by two letters supposedly exchanged by Fretellus and a certain ‘R. Toletano comiti,’ who seems to have encouraged, and perhaps commissioned, Fretellus to write his work. Furthermore, in all of these manuscripts, the text of the Descriptio ends with the following verses as colophon:

Quod tibi presentat, genuit quem Pontica tellus / Archidiaconus Antiochenus Rorgo Fretellus.

[This presents to you the one whom the Pontic land procreated, / the Archdeacon of Antioch Rorgo Fretellus.]

According to Hiestand, these verses can tell us something about the identity of the author. In 12th- and 13th-century charters, the name ‘Pontica’ occasionally referred to the county of Ponthieu, north of the Somme, at which centre is Abbeville. This is the region of Hesdin and there Hiestand found a ‘Frétel’ family whose three sons - Robert, Hugh, and Rorgo! - travelled to the Holy Land around 1119. Two of them later returned home, but the third and youngest seems to have stayed behind. Hiestand identifies this third brother as the author of our Descriptio.1

The verses themselves appear to have been inspired by a passage from one of Ovid’s letters in Ex Ponto (IV.IX.114), where Ovid tells his friend and patron Graecinus of his life in exile far from the city, that is, Rome. 2 Although we can only speculate, it is possible that if Fretellus was indeed the author of this colophon, he chose this intertextual reference to remind his patron that he too, like Ovid, was writing far away from home, perhaps also implying that he was in need of financial help.

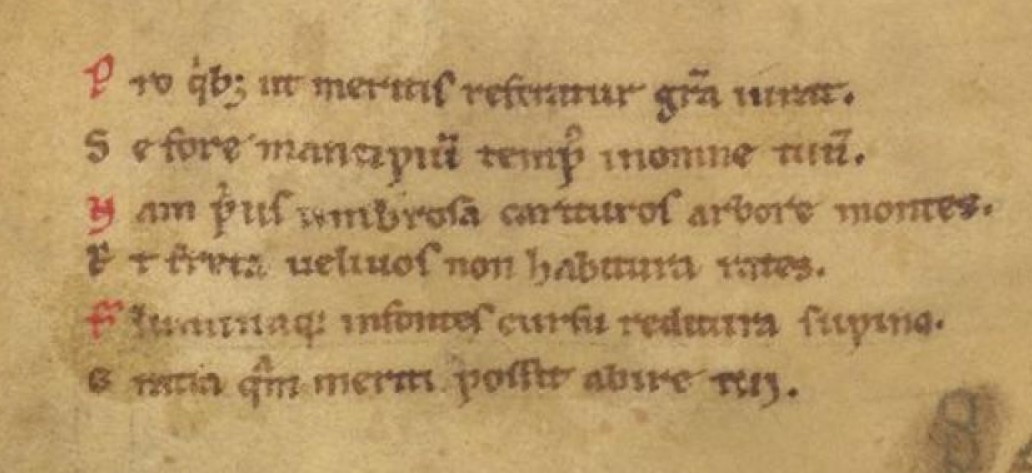

Coincidentally, one of the manuscripts of Fretellus' work dating from the first quarter of the thirteenth century (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 609) contains, in the very end of the codex, a few other verses from Ovid’s Ex Ponto (IV.V.39-44). They were written, in all likelihood, by the same hand that had written the two verses at the end of Fretellus' work. These verses, which serve as a colophon for the whole volume, had hitherto gone unnoticed:

Pro quibus ut meritis referatur gratia, iurat / se fore mancipium tempus in omne tuum. / nam prius umbrosa carituros arbore montes, / et freta velivos non habitura rates, / fluminaque in fontes cursu reditura supino, / gratia quam meriti possit abire tui. 3

[To thank you for these services he swears to be your slave for all time. For the mountains will sooner be stripped of their shady trees and the seas of their sailing ships, the rivers will turn and flow backward to their sources before he can cease to be grateful for your service.] 4

What seems to have happened is that our scribe recognised in Fretellus' colophon Ovid’s work. Perhaps in an attempt to decipher their meaning, he had gone back to Ovid’s Ex Ponto and found his epistle to Graecinus. When his turn came to put an end to his own work, he selected some verses, expressing a keen sense of gratefulness, from another letter in the same volume addressed to Sextus Pompeius, another patron of Ovid. In other words, we have here a remarkable case in which a scribe was triggered to use a piece of classical literature by the text he was copying. This could be one answer to the wider question of the ways in which a text could have influenced its readers in general and, more particularly, its copyists.

Like Ovid and our medieval scribe, we might do well to remember the lesson, and hope with Ovid that none of our modern-day patrons arguat ingratum non meminisse sui [shall call me a forgetful ingrate].5

-

Rudolf Hiestand, “Un centre intellectuel en Syrie du Nord? Notes sur la personnalité d’Aimery d’Antioche, Albert de Tarse et Rorgo Fretellus,” Le Moyen Âge (1994), pp. 7-36, 22-26. ↩︎

-

Ovid, Tristia. Ex Ponto, translated by A. L. Wheeler and revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA., 2014), p. 462: “Pontica me tellus, quantis hac possumus ara, natalem libis scit celebrare dei. Nec minus hospitibus pietas est cognita talis, misit in has siquos longa Propontis aquas.” [“The land of Pontus knows that on this altar I celebrate with what offerings I can the birthday of the god, nor is such service less known to whatsoever strangers the distant Propontis sends to these waters”]. ↩︎

-

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 609, f. 46v. ↩︎

-

Ovid, Tristia. Ex Ponto, pp. 440-441. ↩︎

-

Ibid., pp. 444-445. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 1080/20). ↩︎